Ramblings on how micro services are shaping the future of SQL

by Adrian Pickering, on 10 April 2020

Base Ten is hardly a convenient foundation for how we think about numbers. It is divisible only by 1, 2, 5 and itself. Base Twelve would give us 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 and 12 for segmentation and who doesn't love a clock? A quarter past eleven. Try that with your metric 10-hour day. The revolting French gave it a bash in 1793[1] but it didn't withstand the test of time.

Base Two, native to essentially all computers, allows any number to be represented using just two different characters, 0 and 1. What is more, Base Two lends itself to easier mental arithmetic, or at least it would if we spent half as much effort indoctrinating children in the joys of binary as we do in decimal. How about base 5? No more seven times table, that's got to be of benefit to the sanity of world order.

Yet we stick with Base Ten. Zero to nine, carry a one. Base ten served us well when our imaginations hadn't offered us a more sophisticated abacus than counting on our fingers, but even base two would have allowed us to hit 1023 before reaching down to our toes.

Our broad preference for decimal[2] may or may not have impeded science on this planet, but I can confidently assert that, in hindsight, we probably wouldn't choose it again if we had all of human history to play with. In spite of this, human achievement that depends heavily on mathematics, in the form of scientific and technological advancement, is truly astonishing, and give or take a few morsels, all of that was performed on top of Base Ten thinking.

We may forever be condemned to build for new problems on top of solutions to old problems, long after those old problems have gone away.

Some technologies are burdened by others' legacies, their ancestors solving long-since obsolete problems. The relational database management systems (RDBMS) that power the world nostalgically cling to practices designed to solve a problem that doesn't really exist anymore: efficiently storing and retrieving data from platters of spinning disks of rust by moving tiny magnets as little as possible.

Storage is now cheap and solid state drives reduce the founding purpose of RDMBS to extinction. However, the side effect of years of investment into database technologies - indexing, partitioning, query languages and much more - is a very efficient means of storing and retrieving highly-structured data. The practices and techniques for exercising these technologies are well understood and exploited to great effect.

Enterprises will want RDMBS for decades to come, where the effort in shaping and structuring data more than pays for itself when the returns in processing efficiency are delivered. Smaller organisations, who may value time to market and low-cost staff, broadly have no good reason not to go NoSQL and abandon the RDBMS altogether. Micro services each demand exclusive storage.

Document stores (Couchbase), key value stores (Dynamo), graph databases (Neo4J) and column stores (Cassandra) are so easy for the application programmer to work with and they don't need to worry about n degrees of Normal Form. Concerns of referential integrity - which matter no less than they ever did - are pushed up the stack and become the responsibility of the hosting micro service. Data is replicated but it kind-of doesn't matter as the consumer of the data (the application programmer) makes the judgement on which source is most worthy.

The relationships valued in RDBMS are considered harmful across micro service boundaries

Micro services are a great way to deliver working software. Isolated, free of coupling at the point of testing and deployment, you can make highly robust solutions very quickly, prove them and deploy them. A problem comes with the plumbing: the concern over which data in a conflict "wins" is pushed back up to the application.

A number of modern enterprises, particularly in the B2C space, may work towards "customer-centric architecture". That means there's a customer service and anything that needs to know about a customer consumes that service. You have a customer payment service that looks after the payments a customer has made. It consumes (only - does not extend) the customer service, and offers its own functionality too.

This is mostly a neat fit with SOLID, extensible architecture too - each service is a black box, like using Google or Facebook authentication on your own website - and in return that service promises to never change. By change, I mean it may be extended, but given the same request, the behaviour is consistent. This is in line with the open-closed principle and, logically if not literally, the Liskov substitution principle.

Transactional processing is hard nut to crack in micro services. Logical transactions essentially don't exist, at least they bring complications and the solutions are often not that robust. Each micro service needs to be instructed to reverse the consequence of an action and this is all orchestrated by the consuming application.

I have heard people say monolithic architecture is coming back, I'm not sure it went away, though I suspect micro services are a long way from peaking.

My pet theory - much of what we (as makers of software) do is pretty much boilerplate: the same stuff, more or less, over and over again. Bit by bit, much of the functionality will be replaced by micro services. Google, Microsoft and Facebook authentication are great examples. Why would I want to write my own Auth solution?

Traditional RDMBS n-tier thinking, as opposed to micro service architecture, lends itself to efficiency of data more than it does to horizontal scalability. Micro services and NoSQL solutions are quick to build and cheap to maintain. Finding the balance is where science meets art.

The thing is, programming is fast becoming the new literacy. In Roman times, through and past the Middle Ages, those few who could read and write had a huge advantage over the plebeians and peasants. In the coming generation or so, everyone will be a programmer. It will be as normal a part of professional life as Excel, and, like Excel, 99% of users will get enough out of 1% of its functionality. Still, where there lies an advantage in efficiency of product over speed to market, the older database technologies will still be favoured. Big business will want Oracle until we retire and beyond; such jobs will likely become more scarce and, possibly, higher paid.

The legacy of Base Ten shall doubtless outlive me by some years or perhaps millennia, and although I do not expect the humble RDMBS to survive for quite that long, it will not be disappearing any time soon.

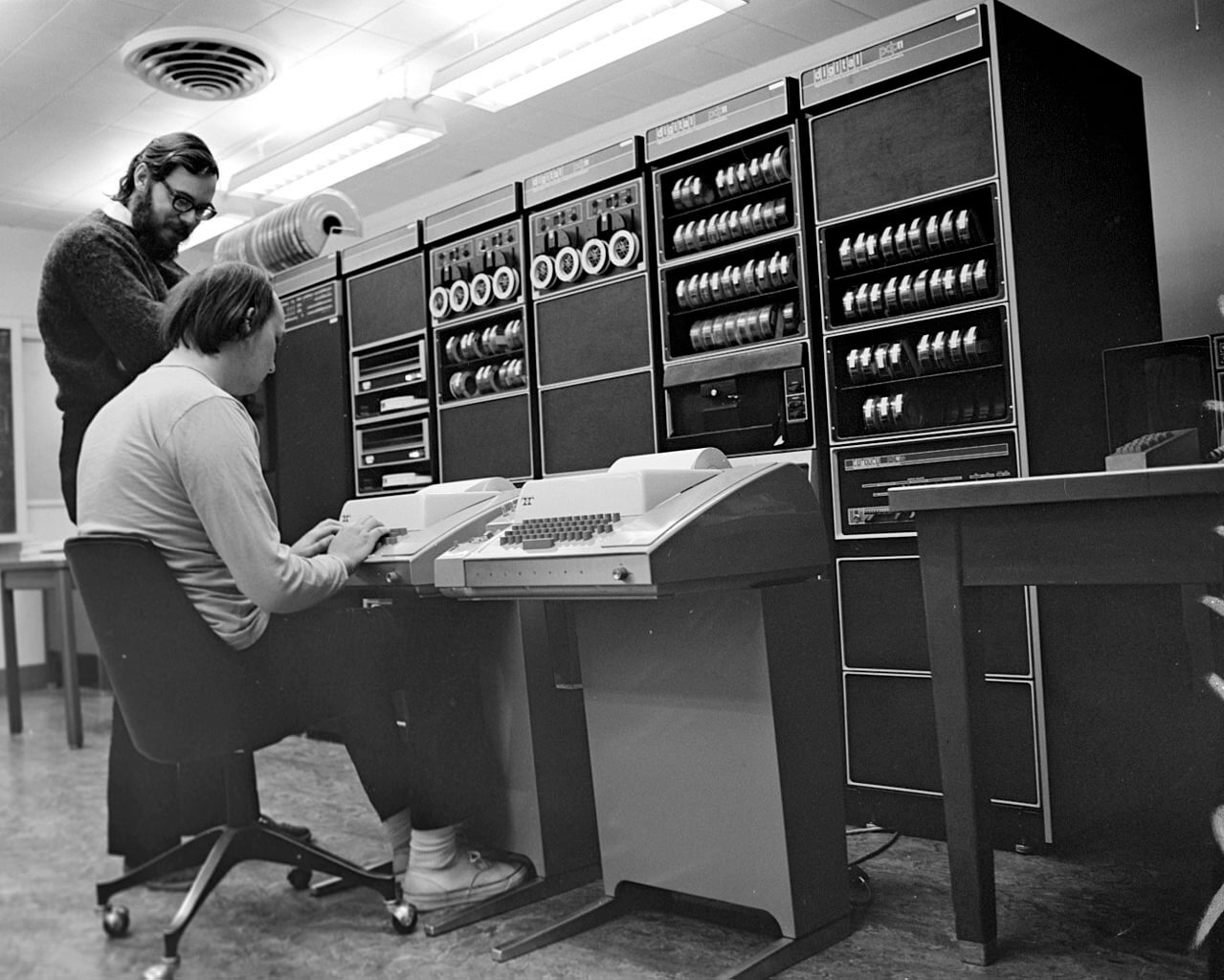

Title Picture By Peter Hamer - Ken Thompson (sitting) and Dennis Ritchie at PDP-11 Uploaded by Magnus Manske, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24512134

[1] https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/32127/decimal-time-how-french-made-10-hour-day At the height of the Revolution, France operated within a decimal time system, with 10 hour days, 100 minute hours and 100 seconds each minute. It wasn’t a great success and was abandoned after a few days. Someone tried again in 1799 and it didn’t do much better then.

[2] The late Babylonians loved Base Sixty. I bet they were never late for anything.

This article was originally published in the nor(DEV): Magazine 2020, grab your copy below:

February 2020 Conference Edition

Featuring; Interviews with the Ladies Hacking Society of Norwich. Articles on Train Wreck, Ramblings on Micro services, Tom's Top Tips for 2020, & What is design?

Download PDF